Enter a search term above to search our website

Pages

News

Star Objects

A huge variety of museum objects will be displayed once Perth’s new museum project is complete. In preparation for this, during my placement here at Perth Museum, a large part of my work has been to carry out condition assessments on the objects. This blog post will outline a brief guide as to what I look for when assessing the condition of organic and inorganic objects.

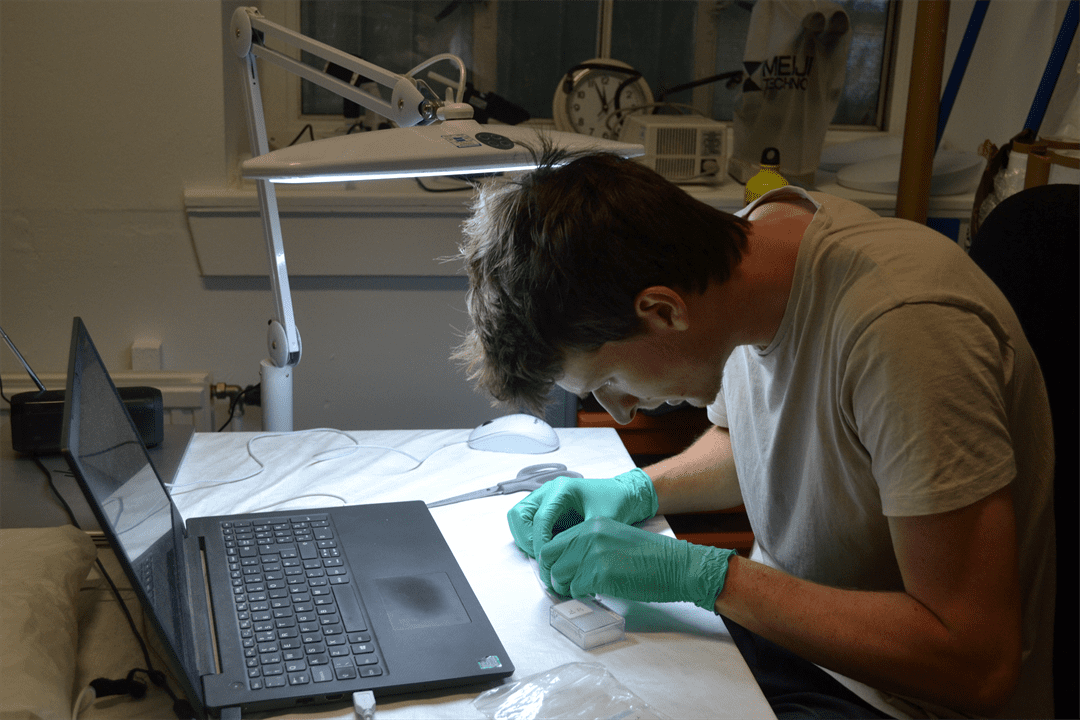

Fig 1: Carrying out condition assessments on artefacts.

The range of metal objects I have examined includes Iron Age rings and Bronze Age copper alloy axe heads. The special, restricted access, metal storage room at Perth Museum is environmentally controlled, keeping the room’s temperature and humidity at prescribed levels. For their long-term survival, metal generally needs to be kept in very dry conditions, and so the Metals Store has a dehumidifier to keep the humidity at a very low level and so to help to prevent the objects from actively corroding. When I’m assessing iron objects, I’m looking for vibrant orange corrosion, evidence of weeping (orange spots staining the packaging), or delamination (flaking), all of which are typical symptoms of active iron corrosion. I’m also looking for past conservation treatments that might be unsightly or too conspicuous, such as excessive lacquering.

Fig 2: Pitting and corrosion on an iron knife.

With copper alloys, such as bronze and brass, I’m trying to differentiate the active corrosion from the stable corrosion. Stable copper corrosion presents itself as a green patina which you may recognise from statues around town or the Statue of Liberty. Active corrosion is a much more vibrant blue/aquamarine colour, an example of which is bronze disease, a highly damaging process that would be of high priority for treatment if found. Lead, being poisonous, always needs careful handling but its corrosion also has stable and unstable states, the latter of which can be a serious health concern.

Fig 3: Stable patina on a copper alloy axe head.

Organic artefacts require different conditions for storage to those for metal objects, needing environments that are more humid. When looking at wooden artefacts, I’m checking for structural damage, such as cracks and warping. I’m also searching for dry rot or mould, which would be of high priority for treatment if found. Finally, I’m looking for any pest damage, such as woodworm, and whether it’s historic or active, looking for any evidence of recent frass (little piles of dust that appear as a pest bores into or out of wood). The Museum has many leather objects in its Organics Store. Probably the most numerous are the medieval leather shoes, excavated in the many archaeological digs that have taken place in town, especially the High Street dig of the mid-1970s. Leather objects can exhibit structural damage, such as cracks and warping, that are unaesthetic but stable, so will be a low priority for treatment. More complicated, however, is differentiating between bloom and mould. Bloom is the result of past treatment failures or efflorescence of salts, whereas mould results from unsuitable storage conditions. Although they look similar, bloom is stable and easy to remove, whereas mould can quickly damage the object beyond hope of repair and is without a doubt one of the most severe agents of deterioration.

Fig 4: Scarring and past conservation treatment on a medieval bowl.

Every object is different, and all require careful consideration and attention to determine whether they’re at risk of, or undergoing, active degradation. Constant monitoring is of paramount importance to ensure items maintain their brilliance for present and future generations. I hope this brief account about conducting condition assessments has been interesting and given an insight into the complex and essential work around ensuring museum collections survive long into the future.